by René Rojas Sep 29, 2023 Amandla 89, International

FIFTY YEARS AGO, CHILE’S ROAD TO socialism suffered a devastating defeat. On September 11, 1973, the Chilean military, spurred by elites, condoned by middle-class sectors and backed by Washington, toppled Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular (Popular Unity, UP). This was a vibrant coalition government helmed by the Communist Party (CP) and Socialist Party (SP).

The coup, which progressives are commemorating the world over, smashed workers’ organisations, popular movements, and democratic institutions. It murdered thousands and sent far more to torture centres, concentration camps, and exile. It ushered in a seventeen-year dictatorship and laid the groundwork for thirty years of post-authoritarian, free-market supremacy in Chile. Just three fast-paced years after its jubilant inauguration, it also appears to have crushed democratic socialist aspirations the world over.

Over the decades, our political vision remains mired in the polarised assessments first offered in the heat of Allende’s coalition’s tumultuous years in power. Either the UP moderated its aims and accommodated elites in order to survive, or it abandoned all compromise and sharpened the class struggle to accelerate decisive confrontation. After half a century, we must move beyond this dichotomised, and paralysing, analysis of the UP’s alleged impasse.

The Left’s return to government offers the chance to take full stock of the Chilean road to socialism. One way to evaluate it is by contrasting its trajectory to that of its present-day heirs. Paradoxically, the Chilean road to socialism was both more effective and viable in pursuit of emancipatory and egalitarian transformations. In 1973, elites employed authoritarian means to usurp power because of the threatening success of the Left and a rising workers’ movement. Today, the neo-authoritarian right is poised to win power for the opposite reason – because of the new Left’s unmenacing failures.

Explanations of the defeat

No remembrance of the Allende’s years is complete without an explanation of the toppling of his government. Two flawed explanations remain dominant: first, observers point to American imperialism; second, critics attribute the UP’s fall to the weakness of its leaders, Allende in particular.

Fifty years ago, Chile’s road to socialism suffered a devastating defeat. On September 11, 1973, the Chilean military, spurred by elites, condoned by middle-class sectors and backed by Washington, toppled Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular (Popular Unity, UP).

Fallible US Imperialism

Against the received wisdom among the global Left, the coup was not the consequence of US intervention and CIA machinations. US intervention only contributed to Allende’s removal once primary domestic factors created the indispensable context for imperialist aims. US efforts to thwart socialist victory in Chile began even before the 1970 campaign. Large amounts were paid to opposing parties. Washington allocated nearly half-a-million dollars to fund Allende’s centrist rival. When Allende was elected on September 4th despite these measures, the Nixon administration approved another ten million, or “more if necessary” to prevent the Socialist’s inauguration.

Washington’s inability to prevent Allende’s victory and inauguration in 1970 underscores the limits to imperialist designs. In the end, of course, US intervention did contribute to the fall of Chile’s socialist government. But outside meddling did not cause its demise.

Dubious socialist timidity

The other prominent explanation for the UP’s failure pivots from external threats to weaknesses inside Chile’s road to socialism. This unpersuasive view holds that Allende determined his own fate by handicapping his radical programme and supporters; his conciliatory constitutionalism was a certain path to disaster.

Some claim that in not nationalising more productive assets, the UP left itself vulnerable to a capital strike by its class enemies. This narrative hardly fits the UP’s actual record.

In addition to nationalizing the copper industry, Allende accelerated the land reform process, all but eliminating the landed class, and vigorously pursued an expropriation programme reaching far beyond the economy’s “commanding heights”. In fact, by 1973, over half of total national output was accounted for by the public sector. During its government, the UP systematically disarmed the ruling class of its economic leverage over the state and society.

Many also blame the UP’s defeat on Allende’s naïve reluctance to unleash working-class insurgency against the ruling class and its institutions. Allende’s task, we are told, was to instigate, rather than restrict, grassroots mobilisation, shifting it onto the offensive against the bases of elite rule. Soviet-style embryos of popular power need to sweep over ‘bourgeois’ ruling apparatuses. Unwilling to meet the moment and drive it toward decisive class confrontation, Allende disarmed workers, rendering them defenseless against looming civil war.

Allende’s was the right road

But this assessment misunderstands the Chilean road’s strategy. The overarching objective by 1972-73 was to substantially advance, not complete, the process of radical reform. With overwhelming support of the workers and the poor, it aimed, as the UP programme put it, to end “domination by the imperialists [transnationals], the monopolies, and the landed oligarchy in order to initiate the construction of socialism in Chile”. The key was to accomplish critical transformative and redistributive reforms that would better position working people and the labour movement to carry out more comprehensive anti-capitalist restructuring.

Allende and popular militants understood the need to preserve the capacities workers, poor people and their parties had painstakingly struggled to develop. Allende’s unwillingness to risk their destruction in a premature and hopeless final battle reflected a commitment to promoting workers’ interests in a manner rooted in the class’s demands and activity. This efficacious adherence to workers’ needs and empowerment is what made the Chilean road to socialism so threatening.

Working class and poor benefited and strengthened

Marchers supporting the election of Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, in 1964. Washington’s inability to prevent Allende’s victory and inauguration in 1970 underscores the limits to imperialist designs.

Allende’s government, particularly its first two years, offered an object lesson in transferring power from the country’s class rulers to organised workers and public management. Before a downturn set in, UP policies facilitated rapid economic expansion and massive improvements for toiling sectors. As workers and the poor’s material well-being improved, their organisation and influence also expanded, affording them enhanced leverage over employers and the wealthy. The mutually enhancing advances—in well-being and power—provoked a short-lived virtuous cycle that translated into growing electoral support for the UP and increasing desperation from elites. The cornerstone for the economic transformations and growth proposed by the UP was the nationalisation of the copper industry. Control of mining and copper exports would underwrite the UP’s redistributive campaigns as well as its programme to accelerate and upgrade Chile’s industrialization.

This dynamised the economy, producing a yearly growth rate of nearly ten percent. Chilean workers experienced the largest wage increases ever during the UP’s first two years. In 1971, real average wages grew by 22 percent. The expansion driven by the UP’s control of the economy brought 1971 joblessness down to 3.8 percent. Near full employment gave workers the leverage to command higher real wages and defend them through 1972.

Meanwhile, social provision expanded for Chilean workers and the poor. After its first full year in power, the UP had elevated public spending on social security to 12 percent of GDP, a jump of nearly 40 percent. By the end of 1972, labour’s share of national income surpassed 50 percent, expanding by a third in just two years! Workers’ newfound leverage also came in the form of recognised popular organisations that the UP incorporated, not without tension, into democratic decision-making processes, both in the economy and in government. Invigorated power resources comprised unions, neighbourhood associations, and workers and peasant councils. All of these played central roles in driving and carrying out the UP democratic socialist policies. When the government was toppled, union density stood at an all-time high of around 40 percent.

Far from demobilising after the UP triumph, workers went on the offensive. The strike wave continued relentlessly. From the 1,819 stoppages during the last year of the Christian Democratic presidency, strikes increased to 2,709 in 1971 and exploded to 3,289 in 1972.

Paving the way for the coup

Clearly, Allende’s adherence to “bourgeois rules of the game” did not bring about the UP’s “self-fulfilling” defeat. The opposite is closer to the truth. Rising working-class influence and the danger it posed to elite domination propelled the authoritarian forces that promoted and carried out the coup. Top business and military officials began planning a coup the instant Allende triumphed. During its first two years, the UP had forestalled these machinations through a calibrated strategy amid rising worker power. The delicate balance entailed fostering transformative capacity, on the one hand, while impairing the opposition’s ability to destroy these capacities, on the other. As Allende laid out in his first speech before congress: If we should forget that our mission is to establish a [society designed for the service of man], the whole struggle of our people for socialism will become simply one more reformist experiment. If we should forget the concrete conditions from which we start in order to try and create immediately something which surpasses our possibilities, then we shall also fail.

Through the tumultuous employers’ offensive of mid-to-late 1972 and until March 1973, the UP’s steady hand managed to prevent the cohesion of an authoritarian coalition while simultaneously bolstering reforms and workers’ capacities. The Chilean road failed when the rise of labouring sectors failed to thwart the precoup alignment.

Success of the counterrevolution

By the next major test, March 1973 parliamentary elections, the combined effects of sabotage of distribution, merchant hoarding and an international commercial blockade had badly eroded workers’ income gains. On top of endemic shortages of key wage goods, rising inflation meant real wages contracted significantly, by 23 percent in 1972 and even further in 1973. Against expectations, support for the UP held, falling only slightly to 44 percent. Compared to 1970, the socialist option gained an even more commanding plurality.

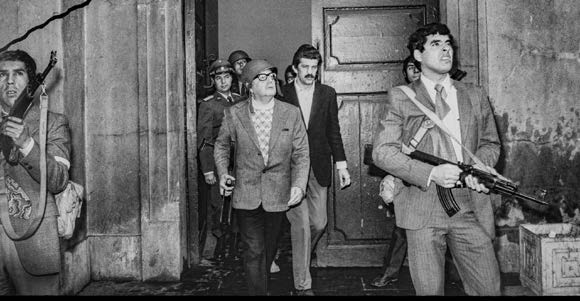

The morning of the coup. The last photo of Salvador Allende (centre of the photo) holding an AK47 that was a gift from Fidel Castro. Allende’s government offered an object lesson in transferring power from the country’s class rulers to organized workers and public management.

Realising their inability to achieve the upper hand politically, professional modernisers joined the economic ruling class’s mission to topple Chile’s road to socialism extra-constitutionally. From that point forward, the country’s politics featured a sequence of manoeuvres to end the government. Truckers paralysed transport again, professional guilds shut down health care and other essential areas, generals rehearsed the coup in the tancazo failed coup, fascistic shock troops rampaged, and congress obstructed the administration by impeaching one minister after another.

By the middle of 1973, the UP’s balancing act had failed: the inevitable impasse had arrived. Either Allende backed down, be it by resigning or offering all the concessions demanded by the opposition, or the looming confrontation would crush socialist reforms and forces. In the end, a version of the latter unfolded. The final showdown for which the MIR and leftwing Socialists agitated turned out to be a one-sided class war. Once in power, however, the junta did not restore the status quo ante. It took total control of the state and society, unleashing a wave of repression that crushed the working class and its organisations and eventually embarking on a radical capitalist transformation.

There was a dynamic road

Although the UP reached a dead-end following the March 1973 elections, the thesis of Allende’s inevitable doom is overstated. Of course, ruling elites may have orchestrated a coup even if the UP continued to foster these crucial conditions; after all, key sections of business and revanchist managerial and military sections were openly calling for it.

But socialist decisions could still decisively shape the outcome. In the crucial moments when elite alignments were taking shape, protecting Chile’s road to socialism necessitated maintaining a wedge between the CDs and economic oligarchs and broadening mass support.

In fact, these dual imperatives were complementary. They rested on the persistent commitment to anti-capitalist policies among the CD’s influential leftwing and among a critical swath of its working-class constituents. Cooperation with the former would have undercut its rightwing leadership’s putschist intrigues, while constructive dialogue with radical Christian workers would have fortified the UP against the coup plotters. Although the UP had indisputably galvanised super-majoritarian backing among wage earners, important sections continued to sympathise with the CDs. Almost the exact same proportion of unionised workers—24.8 percent—voted for the CDs in the momentous national labour confederation (CUT) elections of 1972.

A solid proportion could have been counted on to defend Chile’s road to socialism. Polls that year revealed that one-eighth of CD voters identified as leftists, which in Chile’s context meant adopting anti-capitalist positions. Preserving the affinity of CD voters would have buttressed a pro-socialist bloc.

Restarting Chile’s road to socialism?

Tragically, Allende and his allies were stymied. Hemmed in by the increasing bellicosity of the CD’s rightwing leadership, on one side, and his SP comrades’ intransigent agitation, on the other, Allende found himself out of options. The fruitlessness of negotiations diminished the CD Left’s standing in the party and its influence over its mass working-class base.

The key point is that, however constrained, room existed for ongoing UP advances. The range of possibilities for socialist progress largely hinged on Christian Democratic positioning. And CD decision-making, in turn, pivoted in no small way on how the UP’s strategic approach impacted the party’s relationship with its working-class base as well as its internal disputes. It was a dynamic strategy that preserved the chance of keeping wider constituents in the socialist camp. It also enhanced the UP’s ability to hinder elite reunification behind capitalist counterrevolution.

As with the UP’s initial successes, any breakthrough in 1973 depended on rooting the political and organizational strategies of the Chilean road to socialism even more deeply in even broader layers of, Chile’s working class. Fifty years later, this remains indispensable in any revived socialist strategy.

René Rojas is on the faculty of Binghamton University’s College of Community and Public Affairs and is an editorial board member of Catalyst. He spent years as a political organizer in Latin America.

Republished From: https://www.amandla.org.za/the-chilean-road-to-socialism-50-years-after-allendes-defeat/